Table of contents

What are Electoral Bonds?

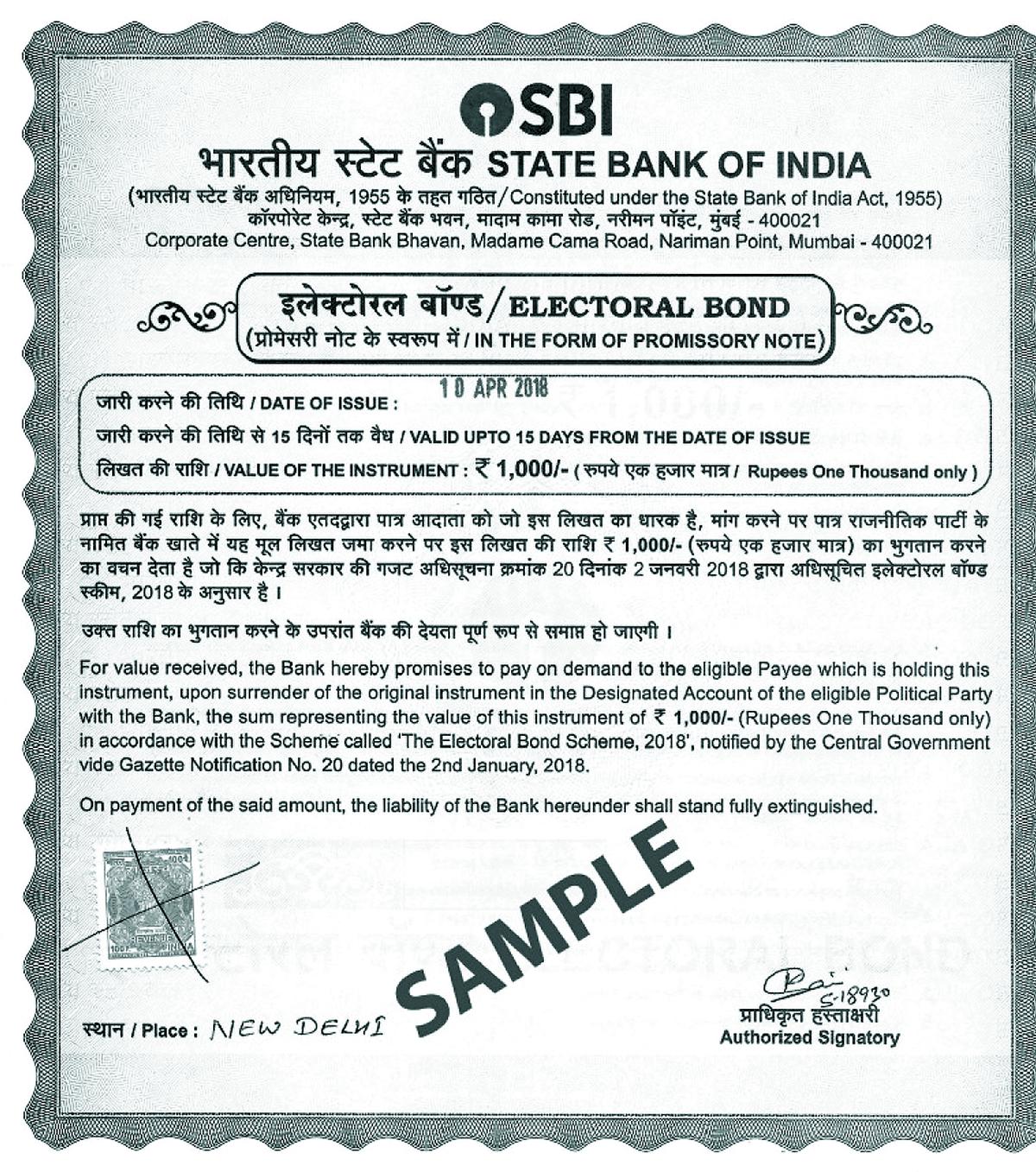

Electoral bonds are money instruments like promissory notes that can be bought by companies and individuals in India from authorised branches of the State Bank of India (SBI).

- Such bonds are sold in multiples of ₹1,000, ₹10,000, ₹1 lakh, ₹10 lakh, and ₹1 crore and can be bought through a KYC-compliant account and donated to a political party, which can then encash them.

- The name and other details of the donor are not entered on the instrument and thus electoral bonds are, in effect, anonymous.

- There is also no cap on the number of electoral bonds that a person or company can purchase.

Background

The electoral bonds scheme was first introduced by former Finance Minister Arun Jaitley during the 2017 budget session, framed as an initiative to ‘cleanse the system of political funding in the country’ and make political donations transparent.

- It was launched through a notification on January 2, 2018, and was preceded by amendments to four legislations through the Finance Acts of 2016 and 2017.

- The Representation of the People Act, 1951, (RP Act)

- The Companies Act, 2013

- The Income Tax Act, 1961

- The Foreign Contributions Regulation Act, 2010 (FCRA)

- Prior to the introduction of the scheme, political parties were required to make all donations above ₹ 20,000 public and no corporate company was allowed to make donations amounting to more than 10% of their total revenue.

How it works?

Every political party registered under Section 29A of the RP Act which secured at least 1% of the votes polled in the most recent Lok Sabha or State elections is allotted a verified account by the Election Commission of India (ECI) in which the bond amounts can be deposited within 15 days of their issue.

- If a party does not encash any bonds within this period, the SBI deposits them into the Prime Minister’s Relief Fund.

- The bonds are usually made available for purchase for a period of ten days each at the beginning of every quarter, i.e. in January, April, July, and October, besides an additional 30-day period specified by the Central Government during Lok Sabha election years.

We can't clear UPSC for you.

But with our personalised mentor support, you'll be ready to do it yourself.

Why was the electoral bonds scheme challenged in court?

Petitions were filed by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and NGOs Common Cause and the Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR).

- Advocate Prashant Bhushan, representing Common Cause and ADR, argued that citizens have a right to information about the parties and candidates seeking their votes.

- Bhushan pointed out that there are roughly 23 lakh registered companies in India. Figuring out how much each company had donated using this method would not be possible for an ordinary citizen, Bhushan argued.

- He added that the scheme would distinctly favor the ruling government of the time

- The guarantee of anonymity would allow the government to provide concessions in the form of licenses, leases, policy changes, and government contracts.

- Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal drew the court’s attention to how the scheme could result in companies failing their duties towards their shareholders.

- Allowing companies to “funnel money” to political parties without any oversight from shareholders denies the owners of said company the ability to decide how their company should act in the political sphere.

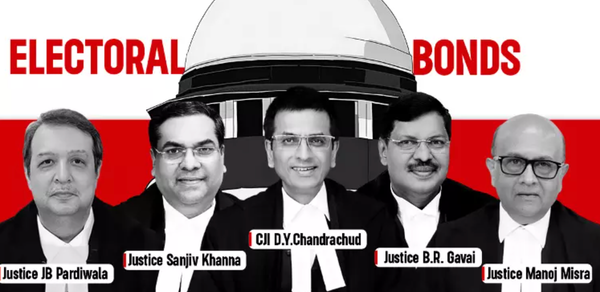

The Supreme Court's verdict

Violation of Right to Information

- The court held that information on the funding of political parties is essential for voting.

- The court found that the scheme infringes on the right to information under Article 19(1)(a), as voters must have access to details about political funding.

Restricting RTI to Curb Black Money

- It stated that restricting the right to information to curb black money is not a valid reason under Article 19(2), and other less restrictive means could achieve this goal without infringing on fundamental rights.

- For the scheme to be considered legitimate, the government scheme would have to essentially satisfy three aspects. This was based on the court’s proportionality test, laid down in its 2017 verdict in the KS Puttaswamy case over the right to privacy.

The proportionality test is a legal principle used to determine whether the actions of a government or law are appropriately balanced with the infringement of individuals' rights it may cause.

- It assesses whether a law:

- Is based on a legitimate objective (existence of a law).

- Pursues a legitimate state interest directly related to the objective (legitimate state interest).

- Is necessary and the least restrictive means to achieve its objective (least restrictive method).

This test was emphasized in the KS Puttaswamy case regarding the right to privacy, highlighting the need for laws to justify the extent to which they infringe on fundamental rights.

According to the Proportionality Test:

- Is there a law? Yes, the Electoral Bonds Scheme was introduced through the Finance Act.

- Is there a legitimate state interest? The government argued curbing black money and protecting donor privacy were goals.

- Is the restriction proportional? This is where the scheme faltered.

Why the Scheme Failed the Test:

- Not the least restrictive method: The Court argued a simple cap on anonymous donations, not complete anonymity, could achieve similar goals.

- Transparency vs. Black Money: Anonymity may curb black money, but it severely hurts transparency - a fundamental right of citizens. The Court deemed this trade-off unacceptable.

- Alternative options exist: The Court pointed out less restrictive options like stricter reporting requirements for larger donations.

The Proportionality Test, thus ensures restrictions on our rights are necessary and balanced. In this case, the Electoral Bonds Scheme tipped the scales too far towards opacity, sacrificing transparency for an objective that could be achieved through less intrusive means.

Justification of Infringement for Donor Privacy

- In the Puttaswamy judgment, the court said that the right to informational privacy includes political affiliation.

- Forming political beliefs is the first stage of political expression, and political expression cannot be expressed freely without the privacy of political affiliation.

- Information can be used by the state to suppress dissent and discriminate by denying employment.

- The court acknowledged the right to privacy in political affiliation.

- The right to privacy of political affiliation does not extend to those contributions, which may be made to influence policies.

- It only extends to contributions made as a genuine form of political support.

Unlimited Political Contributions by Companies

- The court said this cannot be permitted.

- The ability of companies to influence the political process through contributions is much higher compared to individuals.

- Contributions made by companies are purely business transactions made with the intent of securing benefits in return.

As the hearing drew to a close, the bench ordered the Election Commission of India to furnish details of political party contributions via electoral bonds up to September 30.

Source: Live Law, The Indian Express, The Hindu

Previous Post